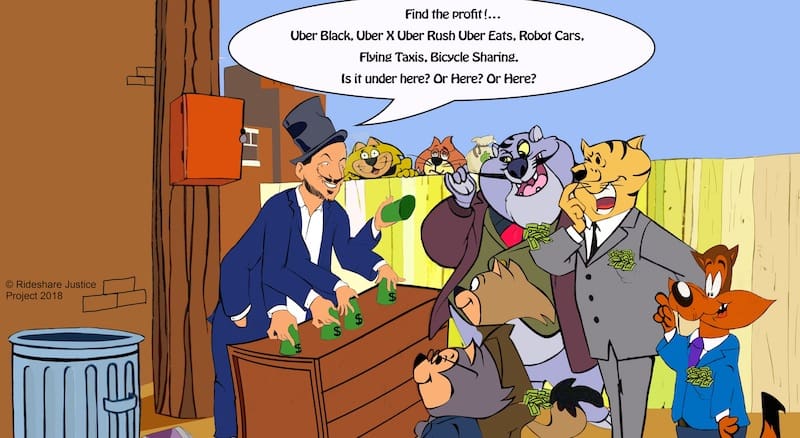

Uber’s Ever Elusive Source Of Profit

Uber’s founder Travis Kalanick’s first transportation scheme was Uber Cab which started in San Francisco in 2010. It was not really a taxi service but an automated way to hire limousine service vehicles at a moment’s notice. He got his idea from a fellow named Kevin Halpern, a New Yorker who saw that city’s black car services sitting idle in the middle of the day after getting their clients to work in the morning. Kevin had pitched Travis to invest in his “Celluride” plan back in 2005 even before the Iphone came on the scene and fostered the mobile app revolution. Within a couple of months of rolling out Uber Cab, Travis looked in his rear view mirror and saw two other SF transportation startups Lyft and Sidecar. Those startups had skipped over needing to work with established limousine services and just used regular citizens driving their own cars. Travis quickly morphed his own service into a new configuration, something he would do repeatedly in years to come as CEO of Uber.

Uber Gets Lean And Expands

Early tests of Uber Cab in SF showed that the most a vehicle could earn was around $32/hr. After paying the driver the minimum wage that was required of limousine services in California plus employment taxes and fees, and then subtracting the vehicle expenses, there was not much revenue left over to support the required tech infrastructure. But, the new model borrowed from Lyft and Sidecar made use of drivers as independent contractors and left it to those drivers to figure out their own pay and expenses at Uber’s fixed rates. The formula took off like crazy across the country and Travis found it easy to raise money from eager investors.

Soon Travis added a messenger service in New York called Uber Rush. Once again, Uber Rush hired bike messengers as independent contractors although NY state had previously classified those messengers as employees with the social safety net of minimum wage and workers compensation insurance. The Uber Rush service was then expanded to Chicago and San Francisco. Then Uber added Instant Delivery intended to bring lunch meals to customers within 10 minutes of ordering. It turned out that neither could make money, so by 2016, both Uber Rush and Instant Delivery were shut down. Uber also expanded into the freight business with Uber Freight but struggled to get it adapted in the close-knit world of trucking intermediaries. Then Uber joined the global movement in food delivery and started Uber Eats to deliver restaurant food to hungry subscribers.

Such moves to expand the gains Uber made by advances in technology are symptomatic the entrepreneurial shifts of the web-based tech boom that started in the mid ’90. The best example if Jeff Bezos expanding Amazon from a book seller to selling everything to delivery services to movie streaming. Uber investors agreed with Kalanick and as Uber expanded its services around the world, money rolled in from VCs, private equity firms, banks and individuals. All of the above permutations of Uber were still just classic adaptations of Uber’s basic business model of combining mobile devices, GPS tracking and the web to add new conveniences to established services.

Uber Develops A “People Problem”

But, by 2015, cracks started to appear in Uber’s business model. Uber faced stiff competition in some of the world’s biggest markets like China and India and was loosing wild amounts of cash in order to lure customers. It also faced regulatory push back in Europe and had to shutter some of its services. But there was a new hindrance, humans themselves. In order to expand the service and retain customers, Uber had to continually lower its rates. That caused driver dissatisfaction creating turnover and resulting in a rash of lawsuits about pay and their classification as independent contractors. Additionally Uber sadly learned that the taxi business itself was rife with accidents and assaults and Uber’s model was not immune to such problems. Uber probably had engineered the most advanced software, assembled the biggest management team, and hired the best lobbyists money could buy but could not control what happened between people in an a rolling vehicle. Travis had discovered what every taxi driver knew, that nowhere else was mankind’s social equation put to such a test as when two strangers got together in a car with one of them behind the wheel. These tawdry issues made it to the press on almost a daily basis around the world and began to tarnish what had been a nearly perfect entrepreneurial fable. Additionally these incidents resulted in Uber pouring out large amounts of cash to settle lawsuits and having to invest in a legal department with hundreds of attorneys and maintain a stable of contracted law firms.

In the summer of 2015, A San Francisco Uber driver won a California Labor Board decision that said she had been misclassified as an independent contractor and awarded her back wages and expenses. It was a small award but it got the attention of the media, investors and regulators Earlier in 2014, Kalanick was became fascinated with self driving vehicles. He believed that such vehicles could be operated cheaper without having to pay a driver. But now it also meant there would be no potential of having to reclassify drivers as employees with the huge additional expenses. It also meant no robberies, rapes or assaults.

In the middle of this quandary, Uber went to dip into the investment community again in the spring of 2016, and it hit its first financing snag. Without big offers from the investment community, it offered $1.6 billion in convertible notes, essentially a loan rather than an investment. The thick printed prospectus for the offer was long on puffery but short on hard financial data. Quite a few investment houses turned down the opportunity to offer it to their clients, but Goldman Sachs picked up the baton and got the round of financing sold. But concerns were growing among investors.

The Big Pivot

By 2015, Kalanick was broadcasting his new love of self driving cars, boasting that Uber could save 1 million lives a year that were lost to traffic accidents and that 1 self driving car could replace 10 human driven vehicles. Uber made a number of PR moves that were intended to rekindle Uber’s affair with the tech investment community. It poached autonomous vehicle researchers, opened tech centers around the US and Canada and put flashy experimental vehicles on the streets of several major cities. It bought Otto, an autonomous trucking startup headed by a former Google lead engineer for self driving vehicles. Uber kept up the drumbeat of futurism and later in 2017 that it would buy a staggering 24,000 Volvo vehicles for their upcoming self driving fleet. The PR worked and Uber received a needed $3.5 billion investment from the Saudi Sovereign Wealth Fund in June of 2016.

What was more important here was that Kalanick’s vision of what Uber was intending to be was no longer a global middle man for connecting available cars and passengers but a transportation provider itself, owning vehicles and pocketing all the revenue. Being a transportation provider was something that Uber had steadfastly denied when pitching itself to politicians and regulators around the world. It needed to do so to avoid the regulations that competitors bore and the costs of drivers working directly for the company. This change was indeed a huge pivot for the company.

Unfortunately, things quickly soured, the former Google engineer was accused of stealing engineering secrets from Google and Google sued Uber, Uber test vehicles were caught running red lights and were kicked out of California. The largest problem was that the horizon for implementing driverless vehicles was actually far into the future and would probably not arrive in time before the firm’s planned IPO in 2019. None of the firms that were developing autonomous vehicles were able to get a car to go through real city streets for more than a couple of blocks without human intervention. Google spun off its own program as a separate company to sell its technology to whoever wanted it. Many experienced scientists said that the research had gotten to the end of the easy part of combining the sensor systems and computers. The hard part lay ahead they said, and would take years, maybe decades to be a reality. Furthermore, near 80% of the public said they did not want to be transported in a hired car without a human driver.

Pivot 2

After Kalanick left in 2017, the new CEO Dara Khosroshahi found that Uber’s rate of growth had peaked at the beginning of 2017, and that Uber Eats, while contributing significantly to the company’s growing revenue was still losing money. Khosroshahi looked at the money that Uber was burning in its self driving program and knew that the company was far behind other development efforts. When he came onboard, he briefly considered shutting it down, but then picked up up Kalanick’s PR baton and continued the shiny narrative of robotic future transportation. If the self driving car was a far fetched idea, the next one Uber was to promote was off the scale.

Pivot 3

At the beginning of 2018, Uber announced that it would develop robotic flying taxis. This brought back images of the covers of Popular Mechanics magazine of the 1950s. Uber named the service “Elevate”. So Uber hired managers and designers and mounted a huge PR program that included sketches of prototype designs, promotional videos, media interviews, conferences, making convention presentations, and creating collaborative agreements with aviation manufacturers, governmental bodies and other technology developers. Uber pronounced that they would have prototypes flying by 2020, just 2 years away. They imagined terminals built on the top of urban skyscrapers taking people from one urban center to another or just home to dinner, just like the Jetsons of 60 TV animation fame. The only problem was that it would take at least many more years than 2 for design, permitting and construction of terminals and airplanes. Furthermore no regulatory framework existed for low flying aircraft or aircraft navigating in urban environments. No air controlling system existed, and the planes were still just images from an artist’s paintbrush. When Uber announced that the planes would be electric powered, someone pointed out that the special batteries selected for the planes did not even exist.

Pivot 4 “The Must Be A Pony Around Here Somewhere”

Bike sharing has been popular and successful in parts of Europe and Scandinavia. Chinese companies picked up the idea and installed millions of bicycles in all the major Chinese urban centers. Many bikes wound up vandalized or thrown into garbage dumpsters, rivers or just stolen. Unfortunately, these Chinese entrepreneurs overestimated the potential use and the government put no limits on the number of bikes to be put on the streets. Quickly huge mounds of surplus bike appeared that were the size of city blocks. Chinese companies tried installing them in US cities without much success but, then along came shared electric assisted bikes and shared electric scooters. Uber and lyft quickly bought into these companies, but in the cities that they were operated in, the rideshare business slowed down as passengers jumped on these cheaper and easier to use rides. Furthermore, these startups have faced opposition from communities that are angered by sidewalks cluttered with parked bikes and scooters. Some cities have banned them when they found riders using sidewalks and colliding with pedestrians.

But Khosroshahi’s PR push seems to be working. On July 26th the investment research group Morningstar issued an effusive financial analysis valuing Uber at $110 billion, almost twice its last valuation of $62 billion just 2 months earlier.

Still, no one is making money in bike and scooter rentals yet, not even Uber or Lyft. And Uber is still losing money no matter how many ways it pivots.

Uber’s plan has never involved turning a profit legitimately, but rather to mislead others into investing more cash into the black hole known as Uber accounting. Since inception they’ve made countless claims, yet still have yet to turn a profit, even when almost all expenses are paid for by drivers.

Make no mistake… Uber’s hopes for a 2019 IPO demand that they cut more corners, steal more money and convince others to invest in unproven “technologies” that will never work, such as autonomous vehicles, all just to hit their proposed IPO, sell, sell, sell and move on, leaving new investors holding the bag.