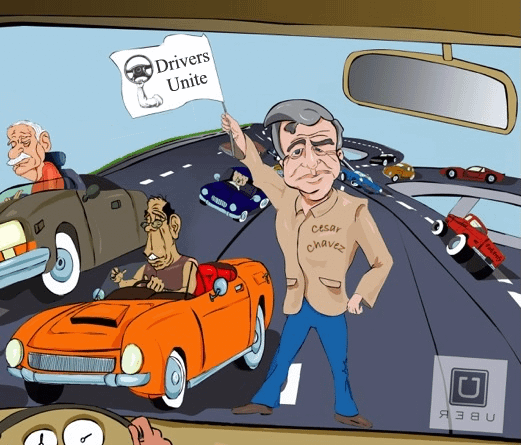

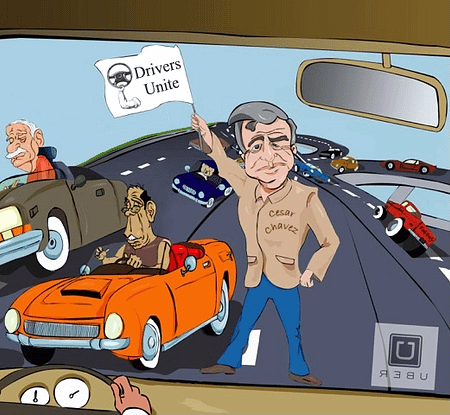

Where Is The Cesar Chavez Of The Rideshare World?

ARBITRATION AGREEMENT

+ CLASS ACTION WAIVER

+ INDEPENDENT CONTRACTOR STATUS

+ IMMIGRANT WORKFORCE

= THE PERFECT STORM OF EMPLOYEE EXPLOITATION

In the spring of 2016 the rideshare company Lyft got an important court victory in a California lawsuit. It agreed to settle a class action lawsuit over the misclassification of its drivers as independent contractors for $26 million. The tentative agreement avoids the reclassification of the drivers as employees. The attorney representing the drivers, Shannon Lise-Riordan has also mounted a parallel suit against rival rideshare company, Uber. The suits are asking for tips and expense reimbursement. In the Lyft case, the plaintiffs faced a more difficult task getting Lyft’s cleverly written arbitration agreement declared unconscionable as opposed to getting the same ruling for the Uber arbitration agreement. The Uber lawsuit will continue and the trial is set for June of this year. The Lyft drivers were left with a fraction of the compensation claimed or the option of filing individual claims and then trying one-by-one to get a favorable settlement in arbitration.

Certainly, one of the key advantages to class action lawsuits is that individuals in the harmed class do not have to initiate any action, they are automatically included in the group of beneficiaries unless they opt out of the group with the intention of pursuing their own cases. This aspect becomes critical when the harmed group is a disenfranchised immigrant workforce. The situation is akin to the Chicano farm laborers that were exploited in California up through the 1960’s because of migrancy, language, poverty, and in many cases lack of documentation. Then in the early 1970’s Cesar Chavez organized the farm workers and got better treatment for a group that had found it hard to speak up for itself. Today, even undocumented workers have workplace and social safety net benefits.

At a time when the U.S. and Europe are trying hard to assimilate refugees and immigrants fleeing strife from Africa, the Middle East and Central America, finding jobs for them is a daunting task. Many of these immigrants have language issues, lack references, work history or education that is verifiable. They are left with few or no job opportunities. Many turn to rideshare companies like Uber and Lyft because those firms hire all applicants with a driver’s license and a clean driving and criminal record. Additionally, their online application process can be completed by a friend or relative with better language skills and can also be easily tricked with false personal information. These hiring processes use no reference checking or work experience vetting and in Uber’s case no interview or ever actually meeting the applicant. Even drivers without cars are offered subprime loans to get them on the road. Unfortunately, the driving jobs, despite the promises, pay poorly. For many of these drivers it is below minimum wage, and for some that is even before taking into account the costs of operating the vehicle.

While angry about the poor wages, most immigrant drivers are afraid to quit or even speak publicly for fear of being terminated. Their new-found job is the only anchor to a new life in the U.S. They also find it difficult to band together to press for changes in their working conditions. With different languages and cultural backgrounds, drivers rely on family and ethnicity based communities for support and interpretation of the new world around them. They also lack a common physical workplace to meet, share their gripes and learn that they are not alone in their dissatisfaction. In many cases the drivers come from cultures of systemic worker exploitation as well as business and government corruption. Few understand Federal or State employment law or know how to access the government agencies that might aid them in getting treated fairly.

Driver applicants are made to read and approve lengthy online independent contractor agreements with arbitration clauses and class action waivers buried in legalese. Few have the education, background or language skills to understand the implications of such agreements. Finally, once on-board and earning far less than anticipated, they find that their independent contractor status keeps them from accessing the remedies that employment law and government agencies provide regular employees. They are also denied the benefit of the legal assistance of a class action lawsuit because of their contract waivers. Finally, if they do decide to pursue costly individual action against the rideshare company, they face an uphill battle against an arbitration system that is tilted in favor of the employer and face crushing legal costs if they lose. Uber’s arbitration agreement even went one step further and provided that the outcome of the arbitration would be kept confidential, creating an underground exploitation scheme that avoids fairness, legal remedies, and public awareness.

The money at stake for tips and expense reimbursement is great. Vehicle expenses represent an average of 30-35% of the gross driver revenue. As a window into the inequities of rideshare driving, look at the case of Uber driver Barbara Ann Berwick. Uber is appealing a California Labor Board decision that determined that she was actually an employee and had been miss-classified as an independent contractor, and so granted her $4000 for vehicle expenses for driving just over 8 weeks. For full time drivers with months or years of rideshare driving, they might be owed substantial sums. Many full time drivers drive between 50,000 and 100,000 miles per year. Berwick’s award was for the IRS allowable deduction of 57 ¢ per mile. That would mean that full time drivers would be eligible for $25,000 to $50,000 reimbursement for every year they drove. In addition to the Labor Board ruling a separate finding by California’s Employment Development Department (EDD) awarded Berwick unemployment benefits after conducting their own review of the details of her work relationship with Uber. Berwick is not alone in her unemployment benefit award, at least 3 other Southern California drivers have been awarded benefits and another driver injured on the job by a passenger is asking the EDD to award Workers’ Compensation Benefits.

In rebuttal to cries of a lopsided payment scheme the rideshare companies tout the part time aspect of the majority of their drivers and the flexibility of drivers making their own hours, saying that 50% of the drivers work 10 hours per week or less. Their promotional materials show drivers that look like the college kid next door, happy to hook up with local travelers when they have a few spare hours to earn extra money. But a recent driver survey performed by the web based blog The Rideshare Guy, rebutted the happy part-timer argument by showing that the 50% of surveyed drivers only did 4% of the total hours worked. 27% of the drivers surveyed drove more than 31 hours per week and performed a majority of the work. Many immigrant drivers drive over 15 hours a day making $3-9/hour as their only source of income for themselves or their family. If they were able to be reimbursed minimum wage for their time and have their car expenses paid, the settlement would be in the $billions and that amount grows larger every day.

The rideshare companies have hired hundreds of thousands of drivers throughout the U.S., and even more overseas. While starting out, the work seems OK, meeting new people and learning how the system works. Many do not understand their vehicle’s accelerated depreciation caused by the additional driving. It silently pulls equity out of the vehicle, turning their car into a sort of pawn shop item. Then, months into the job, a $400 bill comes for tires, $150 for brakes, then worn seats and carpet, shocks and suspension fixtures. By the end of the first year it is no wonder that more than half the drivers leave the job and many more cut their hours back and find another principal source of income. Others have a serious accident and are surprised to learn from an insurance company that their car is now actually worth less than the repair cost and frequently even less than their loan balance. With no financial cushion, these drivers are out of a job and out of a family car. Many have no other choice but to file bankruptcy.

The principal financial challenge for the rideshare companies is to feed their rotating pool of drivers. In the summer of 2015 Lyft reported that for every dollar of gross revenue it spent 2 dollars just on marketing and recruiting new drivers. Uber puts recruiting teams in gas stations, accosting patrons and offering free gas to those that sign up. Radio station ads and billboards that tout inflated potential earnings keep the recruiting channels bringing in replacement drivers.

The world has seen taxi drivers protesting the rideshare companies, now the rideshare drivers themselves are protesting the rideshare companies in India, UK, South Africa, New Jersey, Texas, New York, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles and other cities. These immigrant drivers feel trapped by a system they cannot afford to leave or to stay with. Here is a photo of one of those protests, notice the number of drivers of color or non-European lineage.

Where is this protest? Mumbai, Singapore, Manila? No – New York City!

One slim note of good news, the tentative agreement that Shannon Lise-Riordan hammered out for Lyft drivers includes a stipulation that Lyft pays the arbitration costs for drivers not participating in the settlement, and softens rules on driver termination. Her site, uberlawsuit.com encourages drivers throughout the country to sign up for arbitration should they be denied the benefit of a class action settlement for either Uber or Lyft and for upcoming cases in other states. Now the big question is how does she get these exploited fearful immigrant drivers to take the risk and step forward with their claims? It remains to be seen.

The New York times recently published a three part series on the inequities caused by the growing use of arbitration agreements. The author followed up with an interview on NPR’s Fresh Air that outlined many of the issues. The harm to the legal system has been written about frequently pointing out first, the bias favoring companies and institutions that select their own privately hired arbitrators, then the added burden of legal costs that are foisted on plaintiffs that lose their cases, and the crucial failure to create case law and precedent, the principal tool by which courts develop consistent decisions. These consistent decisions define fairness for society and are a basic principle of justice. But arbitration affects the public in other ways by cloaking bad business practices and the public awareness of litigant issues. The class action waiver allows large corporations to nickel and dime their customers and employees with little chance of ever facing meaningful suits. Who wants go go to a risky arbitration hearing over $3-4 of monthly cellular service fees or a couple of hours of overtime. It is just not worth the risk of a private, one person lawsuit. When we lose the capability of grouping our claims together, we as a society lose the benefit of shaping corporate behavior by bringing bad practices before a public court and getting settlements that create a fair market for goods, services and employment. Many industries like farm work, repetitive factory work employ the least skilled workers and are prone to take liberties with workplace standards and find arbitration an effective tool to avoid repercussions.

The independent contractor model has made a resurgence in the last couple of years as companies like Postmates and TaskRabbit connect needy workers with small tasks like grocery shopping or house cleaning. They have re-branded themselves as the “gig economy” ,putting a bright face on the combination of technology with part time work for the disappearing middle class. Those workers are left without the basic employee safety net that developed countries agree is necessary for a humane and stable work environment.

Arbitration, class action, independent contractor status individually pose difficult questions about the future of work, but when all of these legal threads are woven together they create a perfect storm of exploitation that now allow corporations to hide shady business practices behind the law rather than hide from the law. The Uber and Lyft lawsuits are a good guide. Even if the plaintiffs succeed, they will receive a fraction of what would have been owed in a regular job and it will take years to settle out, long after the rent was due, or groceries bought.

That building storm now threatens the American way of work in a way that we have not seen before. Some commentators write off the change to advances in technology, others believe that a correction in big government is overdue, or that our legal system is stymied in needless litigation and needs to be simplified. Some propose creating new classifications of work, with a “benefits pool” that gig employers contribute for their part time contractors. Others simply ignore the social liabilities that their new age enterprises create. Uber founder and CEO Travis Kalanick, an Ayn Rand fan recently said that Obamacare was great for his workers because its public subsidies make healthcare accessible for his part time drivers. Does he want the public (you and me) to pick up that subsidies tab for his drivers’ workplace injuries and simply skip the mandated worker health care plans?

Looking ahead, others see an end to a “golden era of workplace values” that is being increasingly undermined by global competition. They cite Europe and the Scandinavian countries long held as ideal, progressive societies that are economically stagnant, and other old world countries that lay in a pool of debt for social programs that their economies have failed to support. Even China, a force that spawned much of the change, now has to deal with copycat economies in nearby countries and seen its growth slow. In The U.S. state regulators that have, in the past, brought action against companies that abused labor laws but now stand aside and leave the enforcement to private litigators like Shannon Lise-Riordan whose efforts run up against this new storm front.

These futurists see a new world where economies and work forces are the new armies in a future World War and the battles are for efficiency, technology, competition and survival. They suggest that tough decisions need to be made for nations to remain on the battlefield. I recently attended a presentation at Xerox’s legendary PARC research center in Silicon Valley. A speaker from the U.S. Department of Energy’s ARPA-E Advanced Research Projects Agency talked about his organization’s financial support of advanced hyper-efficient battery research. He spoke of their belief that the country that developed the next wave of efficient batteries would have a huge impact on clean energy, electric vehicles and an economic weapon of significant world influence. He talked of the U.S. losing the development of lithium-ion batteries to Japan and vowed not to repeat the defeat. For a moment it felt like the race between the U.S. and Germany in WWII to develop the atomic bomb.

Perhaps the boatloads of refugees now crossing the Mediterranean or the U.S. border with Mexico are metaphorically jumping into economic lifeboats in addition to fleeing violence. In Europe, many countries initially opened their arms and acknowledged their desire to help, but since Christmas 2015, after the social and economic effects of their goodwill have been publicized, some are closing their borders, others instituting quotas and in some cases sending refugees back across their borders. In the U.S. Donald Trump’s proposal for building a wall along the southern border with Mexico has been met with approval by a surprising number of Republicans. If this is indeed a global economic war how will the U.S. treat its hobbled immigrant workers in a new era of critical competition? Will their plight be viewed sympathetically, will authorities and legislators come to their aid? Or instead, are these exploited immigrants destined to be the expendable first wave in a new assault on workplace standards?

Companies like Uber and Lyft are leading the charge.

Your comments are welcome.

References:

New York Times Three Part Series on Arbitration.